If you’ve ever pondered the perplexing world of fruits and vegetables, you’re not alone. The distinction between what constitutes a vegetable and a fruit isn’t always as clear-cut as we might assume. This article embarks on a journey to decode the mysteries of plant classification, exploring the various factors that determine whether a plant is a vegetable or a fruit. We’ll also delve into common misconceptions, such as whether cucumbers and peppers fall under the fruit category, and what botanical criteria define fruits and vegetables.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Defining Fruits and Vegetables

- The Botanical Classification

- Fruit vs. Vegetable List

- Is a Cucumber a Fruit or a Vegetable?

- Is a Pepper a Fruit or a Vegetable?

- Culinary vs. Botanical Definitions

- Vegetables That Are Fruits

- The World of Edible Oddities

- Confusing Culinary Terms

- Cultural and Legal Perspectives

- Historical Significance

- A Deeper Dive into Botanical Classifications

- Conclusion

Chapter 1: Introduction

The culinary world is full of questions, and one that frequently arises is, “What makes a vegetable a vegetable?” At first glance, the answer might seem simple: vegetables are typically savory and are the edible parts of plants, while fruits are sweet and grow from the flowering part of a plant. But as we’ll soon discover, the reality is far more complex.

In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll journey into the realms of botany, culinary traditions, legal definitions, and cultural perspectives. By the end of this article, you’ll have a nuanced understanding of the intriguing world of fruits and vegetables.

Chapter 2: Defining Fruits and Vegetables

Before we unravel the intricacies of plant classifications, let’s begin by defining what fruits and vegetables are from a culinary perspective:

- Fruits: These are typically sweet or tart, often containing seeds, and are derived from the flowering part of a plant. They are frequently enjoyed as desserts or snacks. Examples include apples, strawberries, and watermelons.

- Vegetables: These are usually savory, though exceptions exist, and they are the edible parts of various plants. Vegetables are consumed as part of main courses, side dishes, or salads. Common examples are broccoli, carrots, and spinach.

However, this basic division doesn’t encompass the full scope of plant classification. The botanical world uses different criteria to distinguish between fruits and vegetables, which leads to some unexpected revelations.

Chapter 3: The Botanical Classification

Botanically, the classification of fruits and vegetables is based on specific characteristics. Here are some key botanical distinctions:

- Fruit: In botanical terms, a fruit develops from the ovary of a flower and contains seeds. These seeds are vital for the plant’s reproduction. Botanical fruits can be sweet or savory and encompass a broader spectrum of flavors than their culinary counterparts.

- Vegetable: Botanical vegetables include the roots, stems, and leaves of plants. These parts may or may not be savory, and they serve a variety of functions for the plant, such as storage or support.

This botanical distinction often leads to surprising revelations about what we typically consider vegetables.

Chapter 4: Fruit vs. Vegetable List

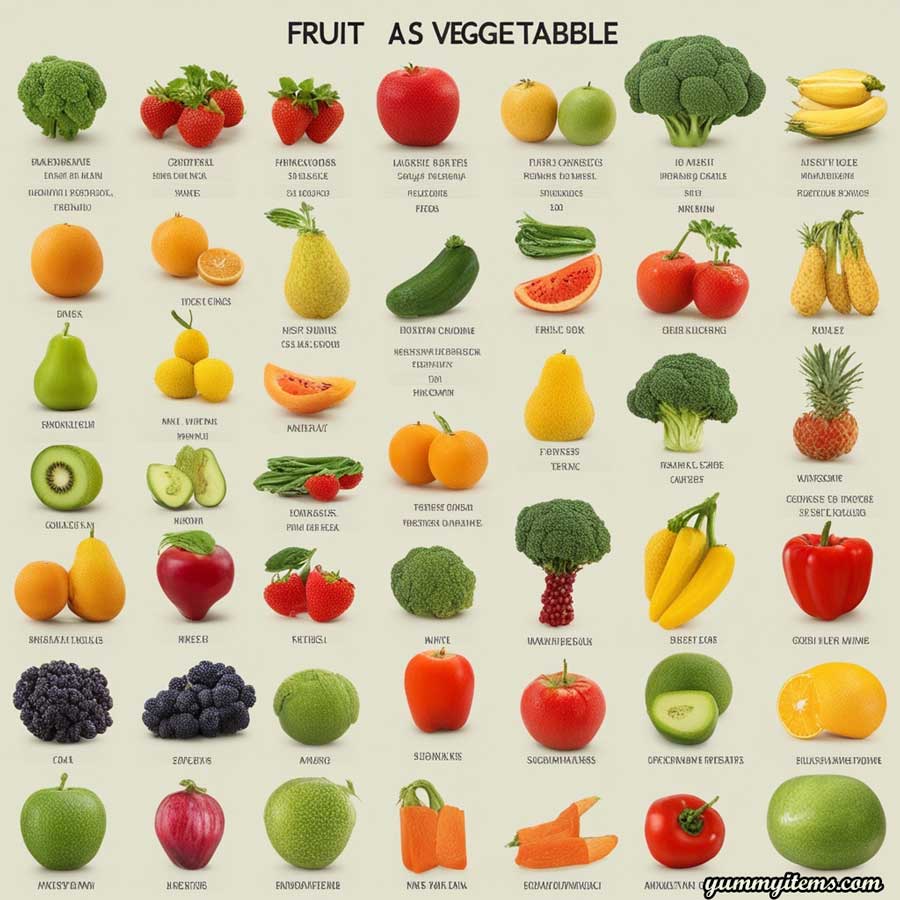

To shed light on the botanical and culinary disparities, here’s a list of common examples and their classification:

- Botanical Fruits: Tomatoes, cucumbers, bell peppers, eggplants, pumpkins, and avocados.

- Botanical Vegetables: Carrots, potatoes, radishes, turnips, and rhubarb.

As you can see, some items traditionally considered vegetables are botanically fruits, and vice versa. This difference arises because our culinary classification focuses on flavor and usage rather than botanical criteria.

Chapter 5: Is a Cucumber a Fruit or a Vegetable?

Cucumbers are a fascinating case study in the fruits-vs-vegetables debate. While they’re commonly used in salads and savory dishes, they meet the botanical criteria for being fruits.

The confusion stems from our culinary practices. Cucumbers are typically consumed in ways we associate with vegetables, leading to their classification as such in everyday language. However, from a botanical perspective, cucumbers are indeed fruits because they develop from the flowering part of the plant and contain seeds.

Chapter 6: Is a Pepper a Fruit or a Vegetable?

Bell peppers are another example of the discord between botanical and culinary classifications. Bell peppers, like cucumbers, meet the botanical criteria for being fruits. They develop from the ovary of a flower and contain seeds, making them, botanically speaking, fruits.

However, culinary traditions often treat bell peppers as vegetables, commonly using them in savory dishes. This misalignment between botanical and culinary definitions can create confusion, even among seasoned cooks.

Chapter 7: Culinary vs. Botanical Definitions

The discrepancy between culinary and botanical definitions underscores the importance of understanding the context in which the terms “fruit” and “vegetable” are used. In the kitchen, we rely on flavor and usage to classify foods, which can lead to different outcomes than those found in botanical classifications.

The dual nature of these terms is an example of how language adapts to human needs, resulting in language that doesn’t always align with scientific precision. Culinary definitions are practical for cooks, but botanical classifications serve as the foundation for scientific understanding.

Chapter 8: Vegetables That Are Fruits

Culinary conventions and botanical classifications often diverge, leading to some well-known vegetables being reclassified as fruits. Here are a few examples:

- Tomatoes: While many culinary traditions treat tomatoes as vegetables, they are botanically fruits. Their versatility allows them to play a role in a wide range of dishes, from salads to sauces.

- Eggplants: These are botanical berries and thus qualify as fruits. However, they are frequently included in savory dishes and considered vegetables from a culinary perspective.

- Avocados: Avocados are large berries containing a single seed, which makes them a fruit by botanical standards. Their creamy texture and mild flavor contribute to their widespread use in savory dishes.

These examples illustrate the overlap and interplay between culinary and botanical classifications.

Chapter 9: The World of Edible Oddities

Beyond the more common examples, there are plants that defy easy categorization. Consider these botanical curiosities:

- Nuts: In botanical terms, many nuts like almonds, walnuts, and pecans are fruits.

- Legumes: Peas and beans, despite being staple ingredients in savory dishes, are botanically fruits because they contain seeds and develop from a plant’s flowering part.

- Pumpkins: While often treated as vegetables in culinary contexts, pumpkins are fruits in botanical terms because they contain seeds and grow from the flowering part of the plant.

- Rhubarb: Often used in desserts, rhubarb’s culinary status as a vegetable stands in contrast to its botanical classification as a stem vegetable.

These examples highlight the complexities and exceptions within the world of edible plants.

Chapter 10: Confusing Culinary Terms

Culinary terminology further complicates matters by introducing additional categories that can blur the line between fruits and vegetables:

- Berries: Botanically, a berry is a fruit produced from the ovary of a single flower, with seeds embedded in the flesh. This definition includes some surprising members, such as bananas, kiwis, and grapes.

- Melons: Culinary language includes melons like watermelons, cantaloupes, and honeydews as fruits, but botanically, they are berries due to their seed-containing flesh.

- Squash: While many squashes are botanically fruits, they are often regarded as vegetables in culinary contexts due to their savory nature and versatile uses.

These culinary terms reveal how human conventions can lead to classifications that don’t always align with botanical criteria.

Chapter 11: Cultural and Legal Perspectives

The distinction between fruits and vegetables isn’t solely a matter of science or culinary tradition; it can also carry cultural and legal implications.

- Cultural Significance: In some cultures, specific foods are recognized as both fruits and vegetables and are celebrated for their culinary versatility. For example, tomatoes are acknowledged as both fruits and vegetables in various cuisines.

- Legal Definitions: The United States Supreme Court once tackled the question of whether tomatoes should be classified as fruits or vegetables for tariff purposes. In the case of Nix v. Hedden (1893), the court ruled that tomatoes should be considered vegetables due to their common culinary uses.

Chapter 12: Historical Significance

The debate over what makes a vegetable a vegetable and a fruit a fruit isn’t a new one. Throughout history, societies have grappled with this issue, shaping our modern understanding of these terms.

Ancient civilizations, such as the Greeks and Romans, contributed to early botanical knowledge. Their classifications, rooted in concepts like culinary usage and plant anatomy, laid the groundwork for modern botanical science.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the debate surrounding botanical and culinary definitions led to the legal case mentioned earlier, Nix v. Hedden, which continues to be cited in discussions of this topic.

Chapter 13: A Deeper Dive into Botanical Classifications

As we’ve seen, the botanical criteria for defining fruits and vegetables are far from straightforward. Within these categories, there are further subcategories, including:

- Simple Fruits: These develop from a single ovary and contain one or more seeds. Examples include cherries, peaches, and olives.

- Aggregate Fruits: These form from the ovaries of multiple flowers. Strawberries are a classic example of an aggregate fruit.

- Multiple Fruits: These develop from the ovaries of multiple flowers that are closely packed together. Pineapples are one of the best-known multiple fruits.

- Dry Fruits: These don’t have fleshy parts. They include nuts, legumes, and grains.

- Dehiscent and Indehiscent Fruits: Dehiscent fruits split open when they ripen, releasing seeds. Indehiscent fruits remain closed, and seeds must be extracted.

Understanding these categories delves even deeper into the intricate world of botanical classifications.

Chapter 14: Conclusion

The question of what makes a vegetable a vegetable and a fruit a fruit encompasses a rich tapestry of factors, from botanical classifications to culinary traditions and cultural perspectives. The interplay between these elements results in fascinating contradictions and complexities.

As you navigate the world of fruits and vegetables, remember that context matters. While botanically precise definitions are crucial in scientific research and understanding plant life, culinary traditions, and our everyday lives often lead to more practical, adaptable definitions. The beauty of this botanical enigma lies in its ability to remind us of the ever-evolving nature of language and knowledge.

So, whether you’re savoring a sweet fruit or savoring a savory vegetable, take a moment to appreciate the intricate interplay of factors that brought that delightful food to your plate. And should you ever find yourself in a spirited debate about cucumbers, peppers, or tomatoes, you’ll be well-equipped to delve into the complexities of what makes a vegetable a vegetable and a fruit a fruit.